Writing – temple bureaucracy – bookkeeping – palace economy – irrigation, management, engineering – archiving – libraries – classification and cataloguing – codes of laws – scribe schools – semiotics and syntax – priests-scholars – abstract thinking. A chapter from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

The fertile soil of Mesopotamia required irrigation and protection from frequent floods. Irrigation created specific socio-economic and political conditions, as maintaining dams and canals demanded collective efforts, engineering expertise, and centralized administrative control over resources. The need for a managerial class emerged – someone had to organize the construction and maintenance of dams and canals and manage water distribution. Besides, knowledge of river cycles was needed. Such knowledge could only exist in the form of magical narratives about the gods whose behaviour defined the seasons, floods, and droughts. These conditions led to the emergence of a ruling caste of priests.

The abundance of crops allowed the farmers to support powerful temples dedicated to the gods, and the priests became temple bureaucrats. This entailed the formation of the first civilization and the first palace economy (or, temple-state economy). To buy water supply and flood protection from the palace, farmers gave part of their abundant crops to the priests as a water fee. This fee also served as a religious offering, an infrastructure levy, and, in a sense, a science tax.

The functioning of such an administrative and economic system couldn’t help but enable bookkeeping. To allow water into certain canals, the priests-administrators needed to know if the farmer or village had paid their water dues. Celestial and river events were also recorded, forming a proto calendar, the foundation of the priests’ knowledge. Economic records accompanied all other business relations. Contracts and bills of debt registered the exchange of products between farmers and craftsmen or between merchants.

In short, the palace economy created the affordance for writing. Writing appeared wherever the palace economy took shape – from Mesopotamia and Egypt to the Indus Valley and Mesoamerica. It perhaps can be concluded that writing emerged only in the conditions of the palace economy with its ruling caste of priests-bureaucrats. Many prehistoric cultures developed systems of proto-writing and pictography, but writing emerged out of economic records and only because they were maintained by a special caste of scribes, who belonged to the priestly bureaucracy.

From a slightly different perspective, these were economic records that, once discovered, evolved in writing and created the class of scribes-priests-bureaucrats and the entire palace economy, the first form of human civilization.

In any case, irrigation, the temple-palace economy, writing, and the special caste of temple administrators who controlled society through the means of writing, emerged together and conditioned each other’s development. Irrigation was the first truly terraforming media project of humans in the most literal sense. Irrigation also terraformed the planet in a figurative sense, as it enabled both the first civilizations and, most importantly, writing, the foundation of all civilizations and of the civilization of humankind. In the spirit of Logan & McLuhan’s article “The alphabet, mother of invention,” it can be said that irrigation was the mother of writing.

By keeping their records, the caste of priests maintained their privileged position in society. This forced them to protect and develop writing as their unique prerogative. From this point on, the ripple effect of media started affecting humans’ mental capacities and social organization. Writing changed thing after thing, creating new human conditions.

First, writing radically transformed the epistemology of sacred knowledge. Prior to it, the shamans of magical cultures transmitted knowledge to their apprentices through oral tradition and magic items. In such an order of things, nothing encouraged the multiplication of knowledge. New knowledge would most likely have been rejected.

Writing, on the contrary, not only preserved all previous experiences but encouraged new records. Once you have a means of recording, you must record something, and this something must be worthwhile, which means selection. On top of this, writing recorded new data and events in an already-sacred form – in the form of sacred signs, thus legitimizing the acquisition of new knowledge. Being recorded, any new experience or event was introduced into the “legitimate” sacred practice for those who read it afterward.

Shamanic teaching became impossible after the introduction of writing. Writing transformed former shamans into priests and temple bureaucrats. Being able to write and read, the priests were encouraged to preserve, produce, and collect records. Thus, for the first time, a scientific ethos emerged aimed at the deliberate augmentation of knowledge.

Writing is not just the recording of data. It requires an infrastructure for collecting and studying what has been already written. In Mesopotamia, the first libraries emerged. The priests and kings hunted for ancient tablets and then studied and rewrote them. By the time of the first famous ancient library, the royal library of King Ashurbanipal (the 7th century BCE), thousands of learned men were involved in library science. Libraries became one of the fundamental imperial institutions that maintained the “monopoly of knowledge.” Ashurbanipal was a brutal despot, but he recognized the importance of not just written tablets but also the extensive and diverse collection of knowledge. His library was reported to contain 30,000 clay tablets.

When librarians were to decide how to stockpile the tablets, they needed to classify them somehow. They started inventing the grounds for the classification of writings, which became the grounds for the classification of knowledge. Knowledge was rationally divided into the disciplines.

The shamans and sorcerers of the preliterate magical cultures simply did not have the need for abstract classification. All things belonged to natural clusters, such as earth or heaven, land or water, etc. All knowledge was syncretic in magical consciousness. All things were in relationships, and proximity or similarity between things defined their nature and their place in the world.

Writing changed the logic of grouping things. The preservation of written data compelled a knowledge-seeker to categorize subjects according to their applicability, origin, or other inherent features. Thus, the very concept of classification emerged along with fragmentation, unification, and standardization. Instead of being defined through their relationship with other things, objects and subjects acquired their own inner ideas. In Mesopotamian and Egyptian libraries, a long journey towards Platonic idealism began.

Writing also required a complex process of learning. For that purpose, schools were organized. “The major aim of the scribal school quite naturally was professional training to satisfy the economic and administrative needs of temple and palace bureaucracies,” writes Logan.[1] So, irrigation was the mother of writing and the grandmother of libraries and schools.

However, teaching writing required an understanding of what it is. How do certain signs represent certain things? What mysterious force ties them together? How do certain words go along with certain words, each time in different conjunctions but somehow consistently? What mysterious force binds them together?

Through the teaching of writing, semiotics and grammar were summoned into being. Writing made people aware of the properties of speech and thinking. As soon as the need to teach and comprehend writing emerged, Babylonian scholars inevitably faced the same questions that de Saussure, Vygotsky, and Chomsky dealt with five thousand years later. As Neil Postman puts it,

Writing freezes speech and in so doing gives birth to the grammarian, the logician, the rhetorician, the historian, the scientist – all those who must hold language before them so that they can see what it means, where it errs, and where it is leading.[2]

Thus, the need of the priestly caste to secure its privileged status brought about the creation of an entire complex of institutions and disciplines to maintain writing itself. Along with libraries, schools, and scribes’ shops, new cognitive activities emerged, such as unification and standardization, the classification of knowledge, the specialization of disciplines, and reflection upon the nature of writing and knowledge in general. Writing transformed the priests into scholars. In discussing the role of writing in Mesopotamia, Logan titles the respective chapter “Introduction to science.”[3] Writing encouraged the specialization and fragmentation of subjects, which eventually contributed to tunnel vision – the ability to focus on subjects isolated from the environment.

With the passage of time, the writing systems of the Sumerians and Egyptians developed phonetic elements that represented syllables rather than words or ideas. The development of phonetic elements was an incredible next leap of abstraction. Humans learned to record something that was not tangible – sounds. In oral and magical thinking, if there is a sound, then there should be someone who makes it. For the oral mind, there is no way to isolate a sound from its source. Early writing consisted of pictograms and logograms that reflected visible and tangible things or their moves and changes, which were also visible and tangible. But sounds, especially those comprised of only a part of a word (such as syllables and phonemes), could not be “isolated” by any sense, including hearing. Recording phonetic elements required exclusively cognitive, not sensorial, operation.

The phonetic elements of Sumerian writing, the first syllables and phonograms, proved that sounds can be “caught” and detached from the speaker. The power of such a revelation might have been truly magical. But the way of realizing it was utterly rational and intelligible. It was discovered that things could be captured not only in pictures but also by the signs recording sounds. Such complexity of intellectual fragmentation and abstraction was certainly impossible for the preliterate mind to comprehend. There had simply been no need for it.

The elements of abstraction, universality, and classification started growing as features of Babylonian thinking under the influence of phonetic writing, as argued by Logan. This not only promoted a spirit of scientific inquiry but also resulted in the Hammurabi code (1792–1750 BCE), a set of 282 rules that established principles for commercial interactions and punishments for misdeeds. The previous oral tradition of legal judgment, mostly confined to the action of authority or collective, was for the first time in history objectivized, structured, conceptualized, and codified.

Following the Hammurabi code, other forms of abstract and codified knowledge appeared, such as mathematical tables aimed at simplifying calculations and tables of weights and measures used in commerce. From the social practices of the priestly class, who maintained writing to secure their privileges, an entirely new environment emerged in which reality was rationalized and brought into order.

However, as Logan states, the lack of fully alphabetic writing prevented the Mesopotamians from achieving the level of pure abstraction typical for the moralistic laws of the Hebrews or the logical laws of the Greeks. For example, the Mesopotamians understood the grammatical classification of words, but they never formulated explicit rules of grammar.[4] The newly invented classification of things and deeds remained connected to practical tasks.

A question may arise: How could writing so powerfully affect society and thought if barely hundreds or thousands of people were literate in the irrigation civilizations? The literacy of the Sumerians and then the Akkadians was a form of craft literacy, as Havelock would describe it, or better to say “sacred literacy”: it was used mainly by the caste of priests for their professional needs. However, the monopoly on knowledge granted political control, and thus the use of the medium became political power, even though only a relatively small portion of the population used this medium.

In his historical study, Jaspers also acknowledged that the influence of writing originated from its use by the bureaucratic elite, and, conversely, the influence of writing gave rise to this bureaucratic elite. “The indispensability of writing to administration led to the acquisition of a dominant social position by the scribes, who formed an intellectual aristocracy,” he writes.[5]

Those who maintained records and had access to them wielded religious and political power. This explains the ripple effect of early writing, even though most of the population was not literate and therefore could not experience the direct effects of writing. Writing influenced society through the elites who used it. Innis noticed this symbiosis of power and writing in his Empire and Communication:

The old magic was transformed into a new and more potent record of the written word. Priests and scribes interpreted a slowly changing tradition and provided a justification for established authority. An extended social structure strengthened the position of an individual leader with military power who gave orders to agents who received and executed them. The sword and pen worked together.[6]

In the cascades of media effects, writing altered cognitive abilities and social structures. Moreover, the changes triggered by writing themselves caused further changes.

A chapter from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

- Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

- Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020)

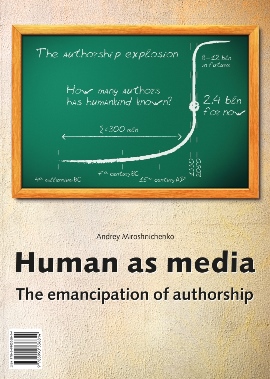

- Human as media. The emancipation of authorship (2014)

[1] Logan, Robert. (2004 [1986]). The Alphabet Effect, p. 82.

[2] Postman, Neil. (2006 [1985]). Amusing Ourselves to Death, kl 402.

[3] Logan, Robert. (2004 [1986]). The Alphabet Effect, p. 81.

[4] Logan, Robert. (2004 [1986]). The Alphabet Effect, p. 85.

[5] Jaspers, Karl. (2021 [1949]). The Origin and Goal of History, p. 55.

[6] Innis, Harold. (1950). Empire and Communications, p. 11. Interestingly, Innis published his main communication treatises, Empire and Communications and The Bias of Communications, in 1950 and 1951, respectively, which coincided with the publication of Jaspers’ The Origin and Goal of History in 1949. While Innis focused on the social and cognitive effects of writing, the consequences he described aligned with Jaspers’ idea of the Axial Age. Thus, the foundations of media ecology (Innis) and Jaspers’ concept of history overlapped from the very beginning, despite Jaspers and Innis being most likely unaware of each other’s works at the time.

Categories: Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror, Digital orality, Media ecology

Leave a comment