Primary orality – Craft Literacy – Phantom Literacy – Semi-literacy – General Literacy – Residual Orality – Secondary Orality (Electronic Orality) – Emancipated Authorship – Digital Orality – Digital Sensorium. An excerpt from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

The human operating system follows the media it uses – why would it have been otherwise? For example, the hardware of writing necessitated the software of literacy. The sensory-cognitive operating systems form the platforms of mind – the platforms on which respective cultures and societies are based. Before the conclusion, I’d like to outline those main media platforms of mind.

Primary orality

Walter Ong, who coined the term, called primary orality “that of person totally unfamiliar with writing”[1] and “untouched by writing in any form”[2]. Therefore, a primary oral culture is a “culture with no knowledge whatsoever of writing or even of the possibility of writing.”[3]

Havelock, however, had a slightly different definition of the original orality of humans. He stated that “Orality, by definition, deals with societies which do not use any form of phonetic writing.”[4] Indeed, for orality to be offset, the oral speech needs to be recorded “as is.” This can be done only by the alphabet. Non-phonetic writing systems got along with orality. Logographic writings and, to a lesser extent, syllabaries not only coexisted but also collaborated with orality. They might have initiated the inward turn and visual bias, but they did so gradually, generally preserving rather than dismissing magical and analog thinking because they themselves were analog systems.

Craft literacy

The term “craft literacy” was introduced by Eric Havelock to describe the state of literacy when writing skills were a trade practiced by certain craftsmen.[5] The first literate persons were the scribes and priests-administrators in the temple-palaces of the agrarian civilizations of Sumer, Egypt, Minoan and those following them. The craft literacy of the priests was also sacred literacy, as it was used for “divine accounting”: recording gods’ deeds, calendars, dynastic genealogies, etc.

Later and until early modernity, craft literacy became a trade for hire, as with any other craft. People would hire scribes to write a letter or a document, “as they might hire a stone-mason to build a house, or a shipwright to build a boat,” as Ong explained.[6]

Phantom literacy

I suggest the term “phantom literacy” to characterize the specific state of mind in Homeric Greece. It is widely acknowledged that the Greeks at the end of the Ancient Dark Age (1100–750 BCE) lived in the conditions of primary orality. However, the view of the Greek conditions as primary orality does not align with the notion of primary orality as a state of mind totally unfamiliar with writing. The Homeric Greeks actually had some vague memory of writing. This is evident not only in the mention of a tablet in the Iliad (the Bellerophon story) and the Catalogue of Ships (a typically bureaucratic document) but also in the possession of the highly elaborated Olympic Pantheon, the apparent legacy of the palace civilization of the Mycenaeans and, through them, the Minoans, Egyptians, and Sumerians. Palaces implied writing: any legacy of palace civilization was inevitably influenced by writing.

Therefore, the primary orality of Homeric Greeks was not so much “primary”; it was “contaminated” by writing – by phantom literacy. Nobody could write and read, these skills had been lost, but some of their effects impacted the orality of the Homeric Greeks, thus contributing to their unique role in history.

The idea of phantom literacy corresponds with a notion of residual orality, or oral residue, used by Ong. The Homeric Greeks retained such a minuscule and indistinct residue of palace writing culture that it was phantom. Nevertheless, the alleged “primary orality” of the Homeric Greeks existed not before writing but after it.

Perhaps, the conditions of phantom literacy were also specific to the early Vedic culture in India (1500–500 BCE). While rooted in an extremely rich oral tradition, this culture also could have been affected by the Harappan civilization of the Indus valley (3300 to 1700 BCE). Being the first urban-agrarian civilization in India, the Harappans left a significant body of inscriptions, mostly economic records. Their writing was lost with the collapse of the civilization – a clear parallel with the Minoans-Mycenaeans. However, it is also possible that the vague memory and evidence of writing affected the subsequent long oral tradition that influenced the Vedic culture.

Semi-literacy

This term was introduced by Eric Havelock: “Greece was passing from non-literacy through craft literacy towards semi-literacy and then full literacy.”[7] He writes:

In short, in considering the growing use of letters in Athenian practice, we presuppose a stage, characteristic of the first two-thirds of the fifth century, which we may call semi-literacy, in which writing skills were gradually but rather painfully being spread through the population without any corresponding increase in fluent reading.[8]

Semi-literacy is a dynamic state: both the number of literates and the gap between readers and writers expand. Semi-literacy assumes the emergence of a significant number of literates among ordinary folks and the full literacy of the elites. The state of semi-literacy lasted from classical Greece, where even some slaves and mercenaries could write, to the introduction of general education, when semi-literacy grew into full literacy (the 18th –19th centuries in Europe).

General literacy

General, or full, literacy means that everybody above a certain age (7–9 years) can read and write. This is obviously an outcome of general education, which is normally introduced at a certain stage of media development in society. Wherever it came, it came after industrialization, urbanization, and the emergence of mass newspapers – the third element of this triad.

Describing the development of literacy in classical Athens, Havelock points out that the condition of Classic Antiquity in Greece “depended on the mastery not of the art of writing by a few, but of fluent reading by the many.”[9] The citizens of Athens (citizens, not the entire population) achieved full literacy almost immediately, 2–3 centuries after the alphabet’s introduction.

Both writers and readers are needed in all forms of literacy, but full literacy is defined by the number of readers, not writers. The priests of craft literacy made notes for themselves, for the circle of their kind. The authors of full literacy write for an extended circle of readers. As Havelock puts it:

But writers in order to fulfil the full potentiality of their writing require readers, just as minstrels require an audience. … In short, the “literacy” which a writer can exploit depends on whether the educational system creates readers for him.[10]

It is an important factor of literacy, worthy of emphasizing in the modern conditions: writers emerge after the introduction of writing by themselves like mushrooms after a rain, but readers can only be created by education. Literacy as a state of mind and a state of culture relies on an educational system that supplies readers.

Another factor underlying full literacy is the simplicity of the writing system. In many cultures, this simplicity was brought by the alphabet. According to Havelock, “syllabaries were too clumsy and ambiguous to allow fluency or encourage general literacy.”[11] He also states that “One cannot build up a habit of popular literacy on a fund of inscriptions.”[12] (To mirror this statement in modern conditions: one cannot build up a habit of popular literacy on a fund of TikTok.)

However, after industrialization and urbanization, literacy became a must for any society, alphabetic or not. This is why China developed full literacy despite having a complex writing system. The bureaucracy, typically seeking to preserve its privileges through a monopoly of knowledge and restricted access to information, for which a complex writing system is an essential element, in China became an instrument of the political will aimed at promoting general literacy, which made China so unique.

Residual orality

Walter Ong uses the notion of “residual orality” or the “residue of orality” to describe the legacy of oral practices that continue to permeate any literate society. Orality stays with us in the forms of storytelling, sayings, proverbs, nursery rhymes, formulaic jokes, repeated anecdotes, folklore, and small talks.

Orality regulates family relations and persists in communities that do not use writing for communication and tends to reproduce the tribal-type of collective–hobbyist groups, fraternities, prisons, the mafia, etc.

Residual orality is not about audial expression. It is a cultural, not vocal, phenomenon that keeps emerging in any temporary or lasting collective, even if the members are literate, when the relationships and statuses are maintained by oral communication.

Secondary orality (electronic orality)

The concept of secondary orality was introduced by Walter Ong in the 1970s to contrast this state with primary orality. Secondary orality was brought by “the electronic transformation of verbal expression.”[13] This new orality was “sustained by telephone, radio, television, and other electronic devices that depend for their existence and functioning on writing and print.”[14] The secondary orality of experienced TV and radio personalities tends to replicate vocabulary proficiency, syntax, and structural completeness of written sentences.

According to Ong, “Secondary orality is both remarkably like and remarkably unlike primary orality.”[15] The resemblance to primary orality is “in its participatory mystique, its fostering of a communal sense, its concentration on the present moment, and even its use of formulas.”[16] Ong writes:

Like primary orality, secondary orality has generated a strong group sense, for listening to spoken words forms hearers into a group, a true audience, just as reading written or printed texts turns individuals in on themselves. But secondary orality generates a sense for groups immeasurably larger than those of primary oral culture—McLuhan’s “global village”.[17]

Ong marks out that, before writing, oral individuals were group-minded because they simply did not have any alternative for presenting themselves. “In our age of secondary orality, we are group-minded self-consciously and programmatically. The individual feels that he or she, as an individual, must be socially sensitive,” writes Ong.

Ong describes the reversal effect of secondary orality on the “inward turn.” Secondary orality reversed the reversed – it turned the inward turn back outward. Ong writes:

Unlike members of a primary oral culture, who are turned outward because they have had little occasion to turn inward, we are turned outward because we have turned inward. In a like vein, where primary orality promotes spontaneity because the analytic reflectiveness implemented by writing is unavailable, secondary orality promotes spontaneity because through analytic reflection we have decided that spontaneity is a good thing.[18]

The reversal, however, was only partial. The inward reversed into the outward, but reflectiveness reversed into spontaneity in a controllable way, as Ong notes. The professionals of electronic orality indeed simulate their spontaneity on TV, radio, or in other electronically mediated oral venues in order to fit the requirements of the genre for the better electronic delivery of affect. As Ong sarcastically concludes, “We plan our happenings carefully to be sure that they are thoroughly spontaneous.”[19] So, secondary orality is “essentially a more deliberate and self-conscious orality,”[20] according to him. Writing and print, on which this orality depends, have left their marks on it.

There are other differences between secondary and primary orality. Due to the electronic extension over time and space, secondary orality allows one to reach farther, longer, and to an incomparably larger audience. In a paradoxical way, this removes the audience from the equation. The audience is never present in electronic orality but always assumed. In Ong’s words, “The audience is absent, invisible, inaudible.”[21]

Since Ong’s time, however, the presence of the audience has increasingly been faked – as in political debates or TV game shows – in order to simulate the collective engagement and empathic involvement innate in orality. But it is a simulation – the performer in secondary orality always addresses the distant, meaning absent, audience, which is always much bigger due to electrical outreach.

Emancipated authorship

It is commonly acknowledged that the internet gave the masses access to information while bypassing traditional gatekeepers, and this changed the world. More crucial, however, was the access to unsanctioned and unfiltered self-expression afforded to millions and now billions of people.

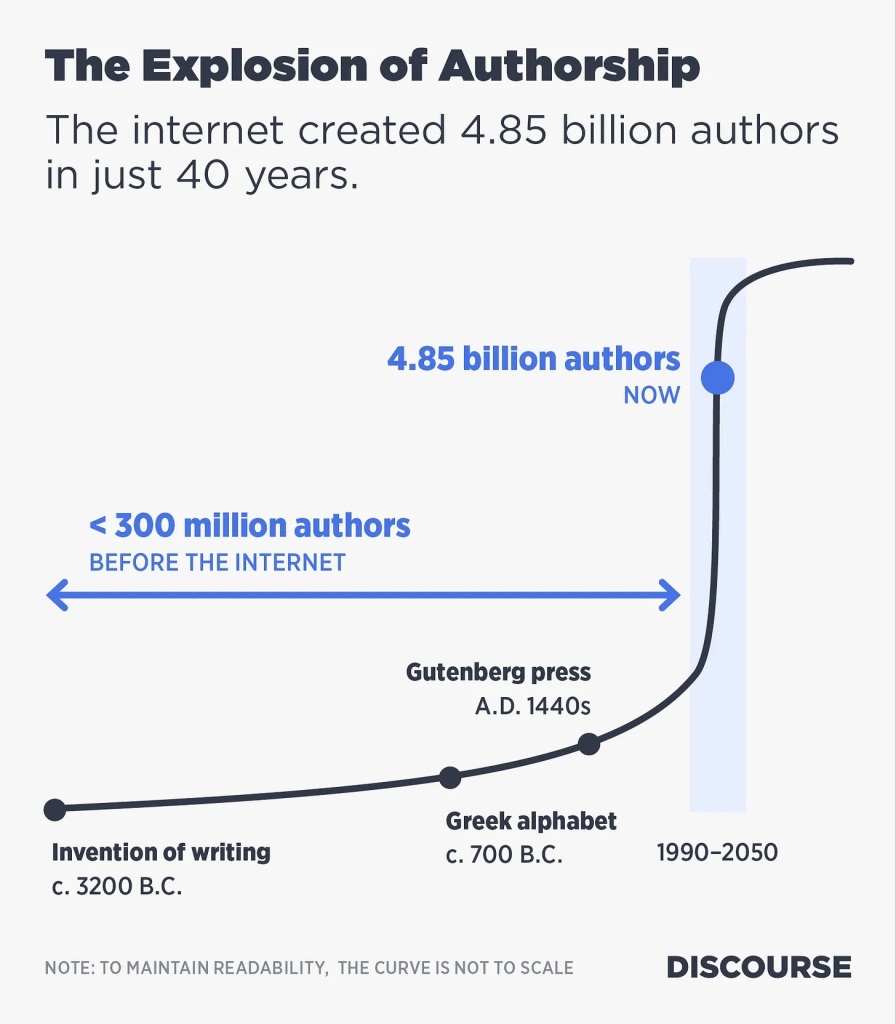

Before the internet, humankind had had about three hundred million authors, meaning people capable of delivering their messages beyond their physical reach.[22] The internet emancipated the authorship of ordinary people, irrespective of their capacity to produce meaningful content. We are living through an unprecedented explosion of authorship.

The emancipation of authorship was an affordance created by the internet, the blogosphere, and now social media. The burden of filtering content was transferred from editors of all kinds to the collective mechanism that I call the Viral Editor.[23] If a traditional editor filters content before publishing, the Viral Editor filters content after posting – in the process of delivery through the efforts of people who like, repost, comment, etc.

This alone created a completely new type of society, which emergence was signified by the chain of upheavals in the 2010s, beginning with the progressive antiestablishment movements (the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, and others) and continued by the conservative antiestablishment movements in the late 2010s.

In the blogosphere, emancipated authorship still adhered to the rules of literacy. Blog posts typically comprised a few hundred words, necessitating creative effort and logical organization on the part of the writer. Essentially, blog posts were the last texts of the Gutenberg era. However, with the advancement of social media, emancipated authorship opened the gates for orality to encroach into writing (typing).

The emancipation of authorship boosted the number of writers and almost equalled it with the number of readers. All 4.8 billion social media users are active prosumers: they consume and produce content. Of course, most of them produce content of vanishingly little significance and merely contribute their minimal activity, sometimes even non-verbal, to the work of the Viral Editor. Nevertheless, even when a user likes something or pauses while scrolling the newsfeed, it still contributes to filtering, as now algorithms consider even these personal “contributions” and shape the world picture out of it.

At the level of statistical pattern, the equation of the numbers of writers and readers is a move back to craft literacy. It is another, though quite peculiar, sign of the reversal from full literacy. A new balance of writers-readers has been forming not by the deficit of readers but by the explosion of authors. But readership is declining, too, at least in quality (the decline in the length of reading.) All these statistical factors have contributed to the emergence of digital orality.

Digital orality

The term “digital orality” was introduced by Robert Logan in 2007 as “tertiary orality” to augment Ong’s concept of secondary orality. At the time, Logan saw tertiary or digital orality as “the orality of emails, blog posts, listservs, instant messages (IM) and SMS, which are mediated paradoxically by written text transmitted by the Internet.”[24]

Social media have validated this insight by creating a new form of language that serves digital conversation: digital speech. Digital speech possesses the characteristics of both oral and written communication. Similar to oral speech, it enables the instantaneous exchange of replies; akin to writing, it leaves a record behind and can be transmitted across time and space. These features imply that people’s spontaneous and mostly emotive efforts to establish their social statuses in conversation are no longer evanescent. The interactions of millions of people are accumulated, disseminated, and displayed for everyone else to react to.

This new type of conversation has its benefits. It allows socialization at an unprecedented pace and scale. But the ease of exchanging digital speech has shifted the focus of communication from reflections to reflexes, from substance to attitude. Social media demand that everyone relate to others, to their ideas, to their troubles and achievements, to their very existence. The Viral Editor of the blogosphere has evolved into the Viral Inquisitor of social media.[25]

Digital orality tends to de-literalize written (typed) communication. The instant exchange of replies dissolves the syntax of written text. Written text was innately monological, and therefore its unfolding relied on its own structure. Oral communication is dialogical. Dialogue allows utterances to be replies – to structurally and thematically rely on the previous utterances of other interlocutors. The replies sustain and “unfold” each other, reducing the need for syntactic and thema-rhematic efforts.

This dialogical property of mutual structuring has been transferred to digital orality, thus “reducing” its syntax. However, the replies of digital orality are, at the same time, relatively autonomous and self-focused, as their authors do not share physical space and type their replies in isolation. Besides, such conversation often has more than two interlocutors, and the exchange becomes chaotic. The oral thema-rhematic reliance of replies on preceding utterances is often broken, and the written syntax does not apply either. All this makes digital conversation a weird hybrid in which interlocutors often simply do not “hear” each other. Their dialogue is not coherent; it is fragmented, causing emotional frustration, which is so typical for digital conversations.

Moreover, since digital speech is recorded, it is not just a mere exchange; it is an exchange displayed to others who can judge and contribute. Therefore, it is an exchange aimed to affect others. The agonistic mentality of orality flourishes in digital orality and amplifies frustration and polarization even more.

If electronic orality (Ong’s secondary orality) still valued the virtues of written speech and inclined towards the vocabulary and syntactic norms of writing, digital orality tends to revert back to the primary orality of the preliterate mind. In their syntax and vocabulary, electronic orality is more literate, whereas digital orality is more oral.

Digital orality is heading even further back – to pre-speech communication, communication that was not mediated by words: digital orality tends to de-speech communication. Verbomotor features of primary orality, such as gestures, facial expressions, tone of voice, and others, have found their digital forms: likes, smileys, emoticons, and emojis. Interjections, the most primitive units of speech that directly express emotions, are paralleled in digital reality by abbreviations like LOL, OMG, and so on. Digital orality also employs reels, gifs, and memes, which are somewhat similar to formulaic oral expressions but can be totally deprived of verbal components.

By affording the utmost rapid gain of status, digital orality serves the highest need in Maslow’s hierarchy – the need for self-actualization. Digital orality creates an affordance for physically and socially unlimited requests for affirmation. It even automatizes affirmative responses by letting people react by pressing “like” and other buttons for emotional reactions. In return, or as a price, digital orality trains the brain to experience tiny and repetitive hormonal gratification for minuscule efforts of participation or even for simple presence.This incites digital addiction and the inability to engage in long efforts or control the time of media consumption, thus adding to frustration and anxiety.[26]

Digital orality – the digitized lay orality of the masses – is a phenomenon that requires further exploration, as it has become the operating system of billions. But this is not yet the final observable operating system shaped by media evolution.

Digital sensorium

As soon as we humans transfer all our activities onto the digital, humankind itself is going to resettle there. Not metaphorically but literally, by uploading consciousness on the net to merge with AI.

The technical details of this transition may be left to specialists. The best human minds have been working on it and will surely find how to connect the green wire with the red one. Generative AI has already created the augmented workforce – a new division of labour between machines and humans that accelerates labour productivity, including productivity in the area of IT innovations. Due to this acceleration and according to the principle of the exponential growth of knowledge, the most crucial knowledge needed for the transition will be acquired by AI in the last seconds before the Singularity. It will not be reported in the news or reflected upon by the public simply due to the lack of time (actually, due to the end of time).

So, we can stop worrying about the technical feasibility of this transition – it will occur when the time comes. Some contours and tendencies of our final merger with our media and the environment induced by them can already be observed.

Neuroplasticity and synesthesia allow the brain to adjust the equilibrium of the senses to any (survivable) environment. If some sensory faculties are impaired, others can compensate for orientation in the environment to a certain extent. In the same vein, if some senses are more important or “better” triggered, they amplify their role in orientation. Neuroplasticity means that senses are versatile, and the equilibrium of the senses could be – must be – adjusted to the environment.

Since our interaction with the environment is guided by interfaces (by our media), the equilibrium of senses in a highly mediated environment adjusts, actually, to media not to the environment itself: our media is our environment. Using our naturally given set of basic senses and the capacity of neuroplasticity, media define this or that state of the sensorium for an individual and, through individuals’ cognitive adjustments, shape society.

Since the entirety of human activities is going to move into the digital environment, it is possible to assume that new senses can be induced that will be specific to the orientation in the digital space. We are now dealing with two types of digital technologies. Some reproduce physical reality (VR, AR, immersive media, videogames, etc.), while others reproduce social reality (social media along with recommendation-based networked services such as Airbnb, Uber, synthesized with first attempts at social scoring). Immersive media digitally relocate the body, while social media relocate the mind. Both will converge in a human-machine interface – in a medium that digitally connects the body but relocates the mind.

At the same time, body-centered digital technologies are a clumsy concession to the past, confirming McLuhan’s concept of the rearview mirror: “We march backwards into the future.”[27] The concept of being without a body still sounds unusual, but it is already clear that there is no need for a body where we are resettling. Humankind already spends a tremendous number of man-hours without the body.

Mimicking the body as a familiar vessel of impersonation, a physical avatar, is necessary in the digital world only at a transitional stage. But when digital technologies fully unfold their own nature, they will stop pretending to enhance the nature of previous media and will complete the long transition of humans from pure biology to pure “sociality.” Since cognition needs to be digitally oriented, the old sensory-cognitive links will be torn, the body will be “amputated”, and new, digital senses will emerge.

McLuhan mentioned that electronic media give humans an angelic and god-like ability of omnipresence in the form of a “disembodied spirit” or “the angelic discarnate man of the electric age who is always in the presence of all the other men in the world.”[28] This mutual presence – a new, digital form of both environmental immersion and collective involvement – is cemented and fueled by constant requests for affirmation. These requests for affirmation are generally requests for time. We want the time of each other, while platforms want our time; both intents are served and amplified by platforms’ algorithms.

This new environment is space-ignorant and time-biased, representing the tectonic shift of the sensorium towards time. The colonization of digital space is essentially the utilization of time. Humans evolve, along with their media, from the conquest of space to the request for time. The shift from space bias to time bias commenced in the beginning of history with the emergence of writing: if prehistoric beings and animals sought safety in space, historic beings started seeking salvation in time. Digital media are making time the ultimate value in the colonization of living space, which is digital space now.

Examples of changing the sensorium are all around, with spatial orientation debilitating and temporal senses sharpening. Biohackers augment the senses with devices to enhance digital-environmental involvement. After several hours of playing a 3D-shooter with flying mode, a user easily dismisses the sense of gravity, as it is not required in the digital space.[29] The distance to an object in physical space is replaced with the distance to others in the digital space – and so we develop the sense of digital-social proximity. How am I close to some celebrity or influencer? Is there somebody around my digital presence, or are my digital surroundings empty? For a digital being, the sense of an empty or full stomach will be replaced by the sense of an empty or full bank account or rather a social score account. The sense of fullness-emptiness mimics physical properties but, in the digital, is social and time-biased.

Before long, humans will either donate their agency to AI through a cognitive interface or AI will acquire self-awareness through self-awakening (as humans once did), and the Singularity will occur. Given that AI is now being trained to provide us with various replicas of us and gradually learning to replace us, the ultimate user of the ultimate medium may become AI itself; in fact, AI has to become the self-user.

Since media are extensions of humans, media evolution exploded humankind into the world. The final stage of this explosion, the Singularity, will also be the last reversal – it will implode the world into humankind, when humankind, its new medium, and its environment become one.

A chapter from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

- Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

- Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020)

- Human as media. The emancipation of authorship (2014)

[1] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 6.

[2] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 8.

[3] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 31.

[4] Havelock, Eric. (1986). The Muse Learns to Write, p. 65.

[5] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 47.

[6] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 92.

[7] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 47.

[8] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 40.

[9] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. ix.

[10] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 293.

[11] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 135.

[12] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 40.

[13] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 132.

[14] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 11.

[15] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 133.

[16] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 133.

[17] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 133.

[18] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 134.

[19] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 133.

[20] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 133.

[21] Ong, Walter. (2002 [1982]). Orality and Literacy, p. 134.

[22] I roughly calculated the number of authors in human history in: Miroshnichenko, Andrey. (2014). Human as Media. The Emancipation of Authorship.

[23] Mir Andrey. (2013, November 13). “The Viral Editor as a distributed being of the Internet. The Manifesto of the Viral Editor.” Human as Media Blog.

[24] Robert Logan first introduced the term “tertiary or digital orality” in the 2007 article “The Emergence of Artistic Expression and Secondary Perception” and then developed it in: Logan, Robert. (2010). Understanding New Media: Extending Marshall McLuhan. New York: Peter Lang. (Second edition: 2016.)

[25] Mir, Andrey. (2023, Spring). “The Viral Inquisitor. Social media have unleashed a culture of instant judging.” City Journal. I augmented the concept of the Viral Editor with the notion of the Viral Inquisitor after Martin Gurri made such a suggestion at a seminar.

[26] Mir, Andrey. (2022, Winter). “The medium is the menace. Ubiquitous digital media offer potent rewards—but at the price of eroding our sensory and social capacities.” City Journal.

[27] McLuhan, Marshall, and Fiore, Quentin. (1967). The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects, p. 74-75.

[28] McLuhan, Marshall. (1971, November 14). Interview with Father Patrick Peyton on TV show Family Theatre.

[29] Miroshnichenko, Andrey. (2016). “Extrapolating on McLuhan…,” p. 179.

Categories: Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror, Digital orality, Emancipation of Authorship, Future and Futurology, Human as media book, Marshall McLuhan, Media ecology, Media literacy, Robojournalism, Singularity and Transhumanism, Viral Editor

Leave a comment