As The Washington Post moved to cut about one-third of its staff, including roughly 300 of its 800 journalists, some critics turned on its owner, Jeff Bezos: given his massive fortune, why not simply absorb the losses and keep funding the paper as a vital institution in the US political and media landscape?

Bezos has a lot of money. (By the way, some other guys do, too.)

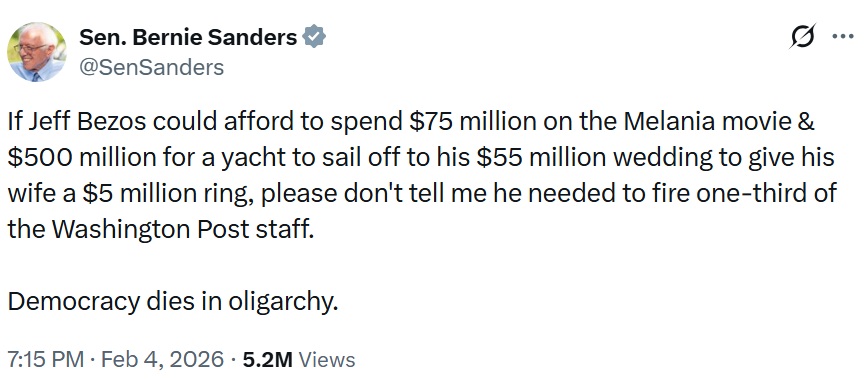

The loudest voice – garnering 5 million views on X in two days – was Senator Sanders’s, who said: “ If Jeff Bezos could afford to spend $75 million on the Melania movie & $500 million for a yacht to sail off to his $55 million wedding to give his wife a $5 million ring, please don’t tell me he needed to fire one-third of the Washington Post staff. Democracy dies in oligarchy.”

From one perspective, the logic seems sound. With losses estimated at $100 million a year, keeping the Post afloat would cost Bezos only 20 rings, mentioned by Senator Sanders, annually. Given Bezos’s net worth of $224 billion, a $100 million loss is roughly equivalent to what his fortune might shed during an ordinary day of market volatility.

And there are many champions of this logic, of course, who easily find uses for other people’s money for the public good. (Socialism might work until you run out of other people’s money – attributed to Margaret Thatcher.)

There are also those who see where this logic leads. Indeed, imagine that Patrick Soon-Shiong, too, were expected to give a small part of his wealth to keep the Los Angeles Times afloat, no questions asked, in the name of the public good. (He has, in fact, continued to do so, though some warning signs, such as layoffs, have begun to appear on that coast as well.)

Imagine then that Elon Musk also must give a small part of his wealth to end world hunger. His fortune is estimated at around $844 billion, while ending world hunger by 2030 would cost roughly $93 billion a year. The arithmetic seems impeccable: he would still remain a multibillionaire. The problem is solved.

The scheme looks feasible, indeed, but with one caveat: to allocate other people’s money justly, those who decide on allocation are always needed – those who “know better.” So a Central Committee become inevitable, and we know who will be there. But, as history shows, those who expect to be the arbiters of other people’s money and fate may soon see fate turn against them, since the Gulag is inevitable in this scheme of things too. But that’s not the point. The point is, under these conditions, why invent or invest at all?

Give us the money and feel free (to go)

But I digressed. Ruth Marcus of The New Yorker elaborated on the idea of Bezos funding the Post through an endowment:

…But there is another model for Bezos to consider: turning the Post into a nonprofit, endowed by Bezos but operating independently of him. For Bezos, this would reduce the role of the Post as a headache and a threat to other, more favored endeavors, such as his rocket company, Blue Origin. For the Post, assuming the endowment is sufficient, it would provide that continuing runway.

…When Bezos purchased the Post, his net worth was about twenty-five billion; it is now an estimated two hundred fifty billion. Why not one per cent of that for the Post, enough to sustain the paper indefinitely? A pipe dream, I know, but this arrangement would make Bezos the savior of the Post, not the man who presided over its demise.

…By that math, Bezos would have more than two millennia before needing to turn out the lights.

Why not, indeed, remain in history as the savior of the Post, not its destroyer. 1% from 225 billion is 2,250 billion. It’s huge, but let’s assume Bezos decides to do that. It can easily generate 100 million revenue per year.

Putting Bezos’s motives, along with his past and present sentiments regarding The Washington Post, aside, will the scheme work? Not in financial terms (it will), but in terms of sustaining the public function of journalism?

Who pays for journalism, and why?

Throughout its history, journalism was paid either from below, by those who wanted to consume news for themselves, or from above, by those who wanted others to consume the right news.

The first type, payment from below, was rare. In its pure form, it existed only twice in the entire 500-year history of journalism: 1) the handwritten Venetian avvisi of the 16th century (before print), and 2) the penny press at the end of the 19th century.

In the rest of its history, journalism was paid from above – by those who wanted to deliver certain content to others, as in the party press, propaganda, or advertising. Of course, there were also mixed forms, such as Renaudot’s La Gazette in 17th-century France, which was sanctioned (literally) from above, by the king, and supervised by Cardinal Richelieu; but Renaudot had a “license” to do business by selling content downward and even early advertising upward. In any case, money-generating control came from above.

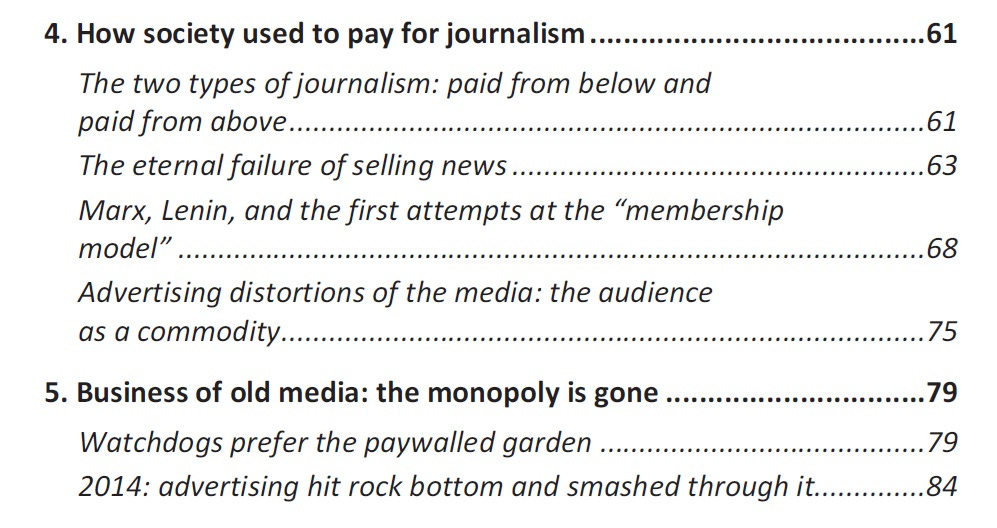

The table of contents of Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020).

Another example is classical journalism at its peak in the late 20th century. It was funded predominantly from above, through advertising, but it also sold news downward, to readers. Because advertisers sought both reputable contexts and affluent audiences, the mass media developed professional standards of objectivity and investigative rigor. The highly revered independence of journalists was not a product of their moral virtue but a side effect of the mass media’s advertising value. In this way, newsroom autonomy became embedded in the advertising business model, despite the fact that journalism was largely paid from above – that is, for delivering content.

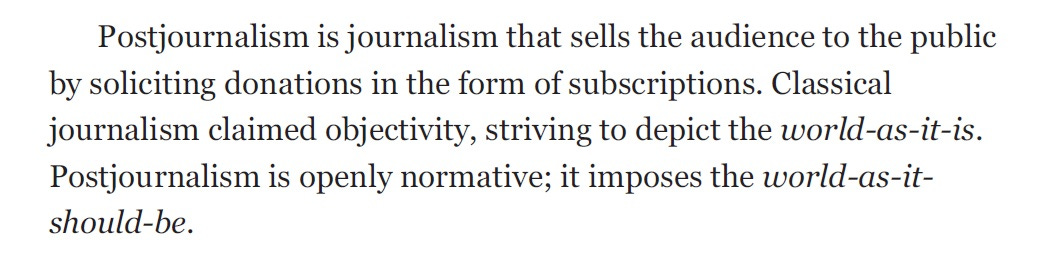

Now, with ad money, news, and audiences having fled to internet platforms, the ad-based business model is gone. The media turned to desperate attempts to attract subscribers. Journalism mutated into postjournalism: mass media began soliciting subscriptions in the form of donations to a cause, which inevitably politicized them.

Those people still willing to pay for subscriptions have almost always already learned the news from social media, so they need journalism mainly to validate this news and to deliver the “right” interpretation to others. In terms of funding, they do not pay for news for themselves – they pay for news to be validated and delivered to others. This is, essentially, payment with a motive from above. But the mechanism of money collection formally remains subscription, that is, from below. This weird mix of a transaction from below with the motive from above emerged because the media learned to solicit donations to a cause in the guise of subscriptions.

Thus, a chimera has formed: postjournalism – news validation paid technically from below but with motives from above, resembling crowdsourced propaganda.

Very few media outlets could succeed under this business model, and only during the so-called Trump bump of 2016–2020, when validation of triggering news about Trump still paid off for the largest news notaries, such as The New York Times. Few succeeded, but nearly all had to switch to this mode of soliciting donations as subscriptions and supplying crowdsourced propaganda. (This also likely repelled Bezos, who was willing to support a great journalistic brand, but not a postjournalist collective.)

What’s wrong with endowment?

Now, where does the endowment model fit into all of this? There is nobody – or not enough people – willing to pay for news from below, so the endowment model clearly represents payment from above. But what are the motives? Normally, from above would mean delivering a curated agenda, as in propaganda or advertising. What agenda will the endowment fund’s board form? Most likely, it will be the same motive as in the past decade: to educate people about what is right. So it’s postjournalism again.

Postjournalism has already eaten away at the remnants of public trust in media. Securing guaranteed funding for something that is neither trusted nor read makes sense for no one, except a group of employed professionals. This entity can continue to exist, of course, as a thing-for-itself, as a fervent circle of self-entitled discourse mongers; but they will monger discourse only among themselves, while producing not even discourse but mostly just outrage outside their circle.

Imagine a media outlet without feedback – at all. An eternal endowment for us, the smartest ones, who know better what people need to know about themselves.

Shielded from any economic feedback, where will the newsroom steer? How will it read the society it’s supposed to serve?

The best-known example of an endowment, The Guardian, struggles with many financial, operational, and journalistic issues. The endowment buffers decline rather than solves it. It cannot really incentivize growth. Operating in a postjournalism environment, the newsroom remains vulnerable to audience capture by its most vocal or ideologically committed readers, and since decision-making is largely insulated from market accountability, there is little to no economic feedback to correct it. And so on. The endowment may preserve (mummify?) media as an institution but not journalism as a function.

(All this, however, may be quite acceptable or even a desirable outcome for people who readily accept the idea of finding a good use for Bezos’s – or whoever’s – money.)

As paradoxical as it may sound, funding is not the issue. Funding will not create readers. The issue with media is not on the side of production – it is on the side of consumption. Therefore, it cannot be solved on the production side, regardless of how much funding or effort is applied. Nor can it be solved on the consumption side. It is not competition over content, as in old media; it is competition for time spent, and new media have immeasurably better time-retention technologies. There are no vacant slots in user time, and old media can never displace newer media in users’ media habits. Regardless of content.

But there is good news. The endowment can indeed help Jeff Bezos pawn off direct historical responsibility for the last years of the noble title. With the endowment, it will be others – likely largely unnamed – who bury The Washington Post. The downside for Bezos is the huge cost ($2.25 billion is still a somewhat sensible amount, isn’t it? It’s a lot of rings) and indirect affiliation with an asset whose political toxicity, under conditions of postjournalism, will grow unchecked if left to its own devices.

Why is he not selling? That’s the question.

Other books by Andrey Mir:

- The Digital Reversal. Thread-saga of Media Evolution. (2025)

- The Viral Inquisitor and other essays on postjournalism and media ecology (2024)

- Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

- Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020)

- Human as media. The emancipation of authorship (2014)

Categories: Decline of newspapers, Future of journalism, Postjournalism and the death of newspapers

Leave a comment