Written words—and especially letters—halted and disassembled the natural flow of experience, reassembling it into the intelligible structure—knowledge. An excerpt from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

…Biologically, life is immersed in the flow of natural cycles and structured by them: day and night, summer and winter, flood and drought, the bodily cycles of hunger and satiation, reproductive cycles, and so on. Animals and primordial humans just went with the flow.

To isolate and preserve valuable experiences that happened in the flow of life, the oral mind fragmented it into events and turned events into stories, which could be recorded through collective reciting. Arresting and capturing the flow of occurrences in separate stories became an important mechanism for extracting, accumulating, and sharing valuable experiences. The fragmentation of reality turned out to be a beneficial strategy: disassembling the flow of events into stories allowed, to some extent, the assembly of new instructions.

The medium – the oral reciting of songs, tales, and proverbs – gave its form to perceived reality. The selected and mythologized fragments of the past natural occurrences shaped their own flow, the flow of oral tradition.

However, the fragmentation of reality was limited by technical features of oral speech: by the turn-taking between interlocutors in conversational exchange or by the time allocated for speaking or singing at the campfire or during a festival.

Writing tremendously boosted the fragmentation of reality. Writing arrested the flow and capture it in tiny fragments of records – words. The alphabet naturally became the ultimate form of this fragmentation, as reality became available for disassembling into the tiniest meaningless quanta, the letters, which could be afterward reassembled into any new meanings. In writing, and especially in alphabetic writing, names that previously belonged to things became words belonging to speech.

Curiously, even after the invention of alphabetic writing, the mind shaped in orality still could not easily detach itself from the patterns of flow. Early alphabetic writing knew no spaces between words and no punctuation. The punctuation signs indicating the end of a phrase emerged, in no small part, due to the use of writing for oral performance: the Greek playwrights of the classical period (the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE) began using marks indicating the end of a sentence to show the actors where to pause.

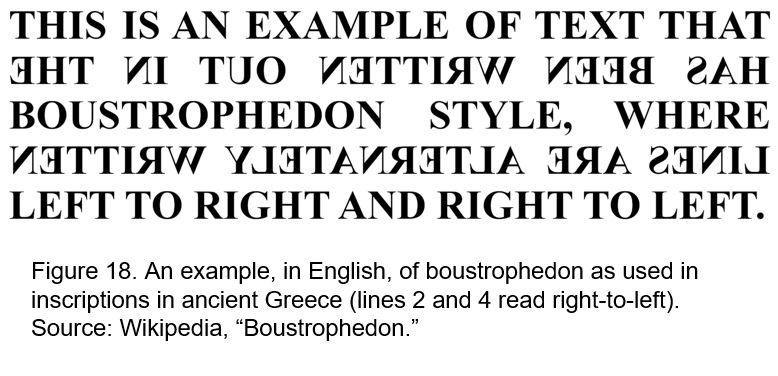

The fact that alphabetic script itself struggled to detach from the continuity of flow is best illustrated by boustrophedon, an early style of alphabetic writing in which letters shaped a sort of “uninterrupted” flow of speech. It simulated the way in which a farmer plowed a field with an ox. The word “boustrophedon” (βουστροφηδόν) in Ancient Greek meant “like the ox turns [while plowing].”

Thus, the fragmentation of the flow of reality by writing was not a natural mental faculty. The natural state of mind resisted it. From my teaching experience, modern students have a hard time fragmenting their writing into paragraphs. I cannot tell if this is an impact of digital media or just due to a lack of writing experience. But it is evident that the segmentation of the flow of speech (and thoughts) into isolated parcels of meaning requires significant cognitive effort and does not come naturally.

With writing, eventually, the natural flow has lost its power over humans. Highly literate society has become capable of not living by the natural cycles of day and night, summer and winter, flood and drought, hunger and satiation. Even reproductive cycles have become manageable. The fragmentation of reality by writing contributed to the divorce of humans from the environment.

The fragmentation of the natural flow was a necessary prerequisite for analytical thinking: it allowed the division of things and ideas into parts in the same way as a child tears apart a toy to see what is inside.

Letters, the primary elements of the however complex whole, provided a model of fragmentation. The alphabet effect of fragmentation was not just subliminal; the Greeks recognized it consciously and almost immediately, perhaps due to their historical shock with the alphabet. Fragmentation naturally led to the idea of the world’s inner structures. What the alphabet did to speech gave a pattern of what thinking could do to the world. As Postman noticed, “Nature was God’s text, and Galileo found that God’s alphabet consisted of ‘triangles, quadrangles, circles, spheres, cones, pyramids, and other mathematical figures’.”[1]

Logan writes:

In addition to serving as a paradigm of abstraction and classification, the alphabet serves as a model for division and fragmentation. With the alphabet every word is fragmented into its constituent sounds and letters. The Greeks’ idea of atomicity – that all matter can be divided up into individual distinct tiny atoms – is related to their alphabet: “Atomism and the alphabet alike were theoretical constructs, manifestations of a capacity for abstract analysis, an ability to translate objects of perception into mental entities” (Havelock 1976[2]).[3]

The fragmented nature of the alphabet and the fragmentation caused by the alphabet to the flows of reality led Marshall and Eric McLuhan to refer to it as the “atomist revolution”:

The change in perception brought about by the spread of the alphabet provided the visual bias necessary to support the atomist revolution and pushed aside the inclusive, audile-tactile orchestration of the senses.[4]

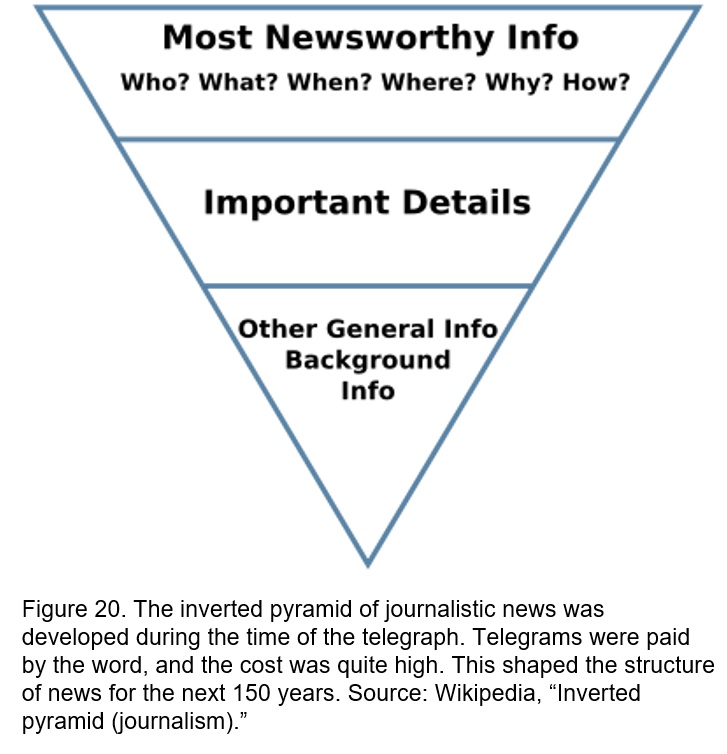

From then onward, the ways people cut reality down into pieces depended on the material production of texts. Scrolls, clay tablets, Roman wax tablets, vellum and parchment codices, printed leaflets, pamphlets, posters, books, and newspapers dictated the size and structure of the fragments of worldview.

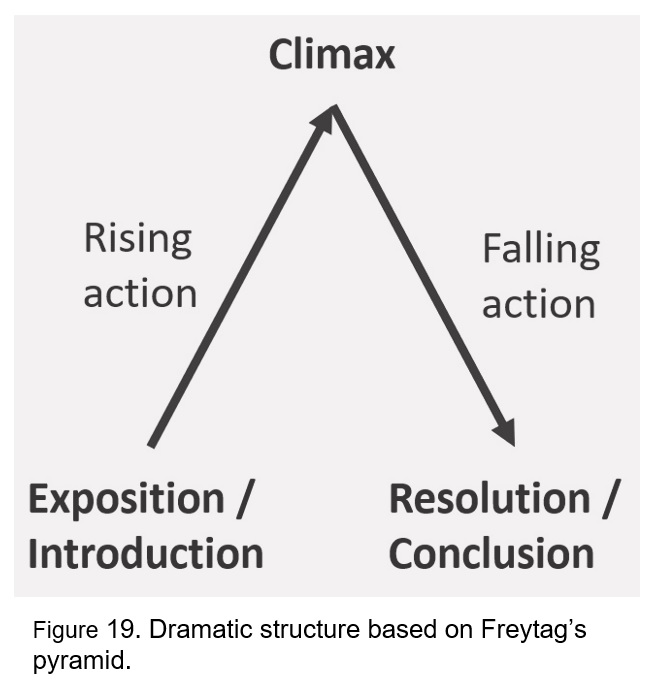

Fragmentation as disassembling entailed re-assembling – intellectually organized structuring. Structuring became the secondary effect of fragmentation. A general structural pattern appears common to all texts: introduction, body, and conclusion. It emerged naturally in the environment of writing but was reflected upon in categories, starting with Aristotle’s Poetics and extending to the modern Freytag’s pyramid of a dramatic arc: introduction, rise, climax, return or fall, and catastrophe.

This structural pattern shaped not just the written reflection of reality but also other human activities. Any meeting, conference, or even sports workout reproduces the structure of “introduction/opening – main part – conclusion/closure.” There is nothing like this in the natural flows of reality, which do not have a beginning, an end, and some logical structure between them. The deliberate structuring of reality is a media effect of writing.

An excerpt from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

- Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

- Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020)

- Human as media. The emancipation of authorship (2014)

[1] Postman, Neil. (1992). Technopoly, kl 507.

[2] Logan refers here to: Havelock, Eric. (1976). Origins of Western Literacy, p. 44.

[3] Logan, Robert. (2004 [1986]). The Alphabet Effect, p. 112.

[4] McLuhan, Marshall, and McLuhan, Eric. (1988). Laws of Media: The New Science, p. 33.

Categories: Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror, Marshall McLuhan, Media ecology

Leave a comment