A discussion about digital orality and reversal from literacy to orality on the internet – from the Worker and Parasite Podcast, January 30, 2024.

In this episode, we discuss Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect by Andrey Mir.

Show Contributors: Jerry Brito, Stan Tsirulnikov.

(The transcript has been created by an AI audio-to-text app and edited for readability).

Jerry: Hi, Stably.

Stably: Good morning, Jerry.

Jerry: How are you?

Stably: I’m well, how are you?

Jerry: I’m good. My “verbomotors” are roaring. Ready to go? Today we’re discussing Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror. Jasper’s Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect by Andrey Mir, who is a friend of the pod. And you know, I feel a kind of self-conscious. We often had the authors of the books that we’ve discussed reach out later. Just, you know, to say thanks for whatever, because the authors listen – it happens, you know.

Stably: It does. It’s shocking!

Jerry: But I don’t think ever before have I been certain that an author was going to probably listen to what I was about to say.

Stably: Okay. So scary,

Jerry: But you know, we’re going to be as usual: we’re gonna give the unvarnished view

Stably: Until the check clears.

Jerry: Very good. So, Stably, what do you think?

Stably: I enjoyed it. My sensorium is brimming with information. My “verbomotor” is burnt out. I liked it a lot. You know, there’s a lot in here – there’s a lot to unpack. I’m not sure if I actually unpacked it all. I think, if I may, in terms of organization and style, it’s an improvement on his first book that we read, Postjournalism. Although that one was also fun.

Jerry: Yes, Postjournalism. Which I don’t recall being difficult to read. I remember loving that book.

Stably: Oh, I liked it, too. It was just very long – I think it was even longer than this. So, anyway, I enjoyed it. I think it would be fruitful for people who are interested in this sort of things. I guess it should be everybody. If you’re into how the internet is changing society, and media study, and all that. I think everyone could benefit from reading it.

Jerry: Yes, that’s what’s interesting about this book – and Postjournalism, too – but more about this book. It’s in the same realm as Martin Guri’s Revolt of the Public. Yeah, if you’re interested in media studies, in media ecology, it is this book. I think, actually, the book is about humanity and its fate. It’s kind of like evolutionary biology: it puts everything in that and explains everything.

Stably: Yes, this would be like if any of these magazines, like the Atlantic or New Yorker, with their longreads, as the kids call it, printed it and have people chew on …

Jerry: Yeah. Because, you know, as people say, since 2016 everything has been weird. There was a great tweet on January 1: “Today we enter the eighth year of 2016…”

Stably: Yes, it’s great.

Jerry: I think people are confused about what is going on. Something’s happening, but we don’t know what it is. And, you know, this book – same as Revolt of the Public – kind of explains what is happening. At least it offers an explanation.

Stably: Yeah, I think it’s in our wheelhouse, right? It’s the kind of book that would have been talked about a lot more in the late 80s. It’s a Big Idea book – with capital “b”, capital “i” – and those were fun. I’m not a media ecologist of any kind, I don’t know how accurate he is, the usual caveat… But I think there’s a lot to think about and noodle over. And it was a lot of fun. I feel like I’ve learned things, Jerry.

Jerry: All right. Well, Stably, would you be interested in telling us what the book is about?

Stably: As usual, it’s in the title, right? Well, actually, it’s not…

Jerry: Yeah, I was gonna say, this is not. I can tell this book did not get the major-publisher treatment, because the title doesn’t tell anything to a layperson.

Stably: Let me know… I haven’t checked, I’m very lazy, I’m the parasite, right? Is this been published-published? Or is it just kind of released on Amazon or something?

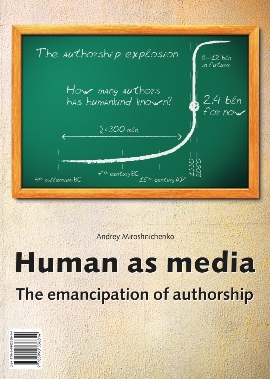

Jerry: I thought it was impolite to ask. But I could detect no publisher. Which, by the way, fits his other idea – what was it… “The emancipation of authorship,” right?

Stably: That’s right. So, I think Andrey Mir’s main hypothesis is that digital media are reverting humanity from the literate age back to the oral age. To historical periods, as defined by Karl Jaspers and Robert Logan. Karl Jaspers was a German philosopher and historian. He had this theory of the Axial Age, which Andrey Mir uses and elucidates. And then Robert Logan with Marshall McLuhan had the theory of the alphabet effect. So, Mir kind of plots out how all of humanity has developed over last couple of thousand years as literate creatures. It’s actually what makes us humans. And now, in a lot of ways, digital media and digital communication are reverting us back to the pre-literate, oral age. That is his theory.

Jerry: Right. And basically, Karl Jaspers in his book about the Axial Age, called The Origin and Goal of History, says that there is pre-history, history and world history. Jaspers thinks that there was a moment in time that occurred in the 8-3 centuries BC, when simultaneously appeared Confucianism, Buddhism, Judaism, and the Greek philosophers. It was an axial point that completely changed the course of history. Man stopped being tribal and magic-oriented and became more individualistic and abstract-thinking.

As Andrey Mir points out, Jaspers could identify the axial point and discuss how something happened that changed the course of history, but he didn’t tell you what it was and why it happened. Jaspers had some theories that he tested, like: maybe it was the domestication of horses… But he didn’t really offer an explanation.

And then fast forward to the 70s in Toronto, where Robert Logan, a physicist, tried to figure out why certain cultures took off technologically whereas others didn’t. And with his pal, Marshall McLuhan, they figured out that those cultures that took off had one thing in common – an alphabet.

Stably: Except for…

Jerry: Except for China, of course… The alphabet theory answers Logan’s question about technological civilizations, but it doesn’t fit Jaspers’ theory about the Axial Age. Logan was basically saying, you know, the Chinese invented gunpowder, and money, and all these other things, like pizza – before anybody else. But none of these guys, like Newton or Copernicus or whoever, were Chinese. So – how come? And the answer that McLuhan and Logan came up with was the alphabet.

But the alphabet does not fit China. And so, basically, Mir says that the thing that changed everything in the Axial Age, which Jaspers could not identify, was writing. When you learn to write, it changes the course of history. Because the media change the environment and people and the ways people think. So, it was writing, and especially alphabetic writing – when you are actually recording speech. And he gives a lot of reasons why it happens – you should really read the book to find out why.

Stably: Yes, and the biggest reason is that alphabetic writing allows writing communication to spread beyond a closed priestly class.

Jerry: But also because it’s not merely a pictogram or a hieroglyph. When you still reading pictograms, you think in concepts, rather than reading the actual speech…

Stably: …Yeah, like deciphering. You’re always interpreting. So, yes, it’s all very interesting. We’re not doing as good a job as he did.

Jerry: Oh, yes. So, writing started history. And then world history comes with the printing press. That’s what begins globalization, and it has all kinds of other media effects that he talks about. The main point is that oral civilization is incredibly different from literate civilization. One could argue that literate civilizations are more advanced and have produced much more wealth – that’s for sure… But since the invention of electronic media, and especially now with digital media, you’re basically getting a return to orality. And we’re losing everything that is valuable about literate society. I’ll stop there and let you fill in.

Stably: Yes, you did a pretty good job summarizing. I’ll just mention some of the things that kind of jumped out at me. The whole Axial Age thing is, you know, one of those big ideas that historians and other smart people like to argue about. Karl Jaspers didn’t just make it up, but it was one of those books written in the mid-20th century that were very unifying, and there may be some holes in it.

As Jaspers described, there are these three periods,. One is pre-history, which is most of human existence. And then history, which began only with writing in ancient Egypt and Sumer. Before that, we have broken pottery and skeletons and burial mounds, and that sort of things – but that stuff isn’t history yet, because there is no writing. People from back then are not communicating to us. So, you know, that’s an interesting concept.

And, like you said, world history began a hundred years ago. Jaspers wrote his book right after WWII. I think his idea is that world history has culminated by his time. WWII was a truly global conflict, and that was an indication of how connected everything is and how we truly are living in world history.

Jerry: It started with the wars of religion, I guess. The point is that the printing press allowed speech to travel and ideas to move through space. But prior to that, basically, all history was kind of local history.

Stably: Yes, exactly. History was like: this is happening in China, this is India, this is Eastern Europe, this is Western Europe, etc. And they never really met or connected. It’s an interesting idea, at least to me: WWII showed that now this is a fully integrated world. Essentially, no corner remained untouched. …What else? I mean, you know, you’d have to read the book – we can’t possibly go into all the details and the theories of communications he touches upon…

Jerry: Yes, it’s just so much. It’s page after page of interesting things that I didn’t know or connections that were made for me. I’m sure I’ve forgotten half of them because they’re kind of not necessary, but they’re all there. This is why I think, with all due respect, you can tell this book probably wasn’t really edited by the kind of editor who would edit a book for the mass market. So nothing was left on the cutting room floor.

Stably: Yes, he didn’t kill his babies. Which is charming, but yeah, anyway – all that was very interesting. He brings in a lot of different thinkers. It’s not just Jaspers and Logan. It’s a bunch of other people that I think were way bigger back in the day, when people were really into media studies and media ecology. It just makes me think of Woody Allen, right? You need to be really into this sort of thing.

Jerry: “You know nothing of my work…” <quoting McLuhan from Allen’s 1977 movie Annie Hall>

Stably: Yeah, the 70s and 80s. And I guess these guys aren’t really household names anymore.

Jerry: Well, there is also Ong who coined the term “inward turn”, which, I’m sure, people are familiar with.

Stably: Are they? Okay, I guess, maybe. I mean, yeah, it is just a trunk full of interesting stuff. And, you know, Mir does a very good job of making you interested in these topics. He’s very excited about this stuff, and it comes through very well.

So, we’re reverting back to a prior age. Alright, so terrifying.

Jerry: So, what does that mean in practice? What is an oral civilization like? Well, it is immersive. You’re part of a collective, you’re part of a tribe, and you’re never alone. There’s nothing you can say that isn’t gonna be heard by others. Which is interesting, right? Because I think that kind of kills any idea of individuality. Basically, whenever you’re talking, you’re always trying to get affirmation from people and trying to affirm your status or trying to claim your status. Mir talks about the “agonistic mentality”: everything is always like an argument – is that the way to put it?

Stably: I think that is, yes.

Jerry: And there’s no knowledge, there’s wisdom, right? And that wisdom is kind of transmitted through stories that are repeated over and over orally, and that the community just knows the stories. We would listen to the priest who has memorized them and can tell the story. And there’s no questioning. There’s just repeating, because repeating and listening and repeating again is the only way you can transmit the knowledge. If you take a step back, this sounds a lot like Twitter.

Stably: Yeah, sounds like most social media. Or even electronic media in general.

Jerry: Right? But especially on social media, where everything you say, you’re never alone. Whenever you speak, you know that you’re speaking to the world, and it can be heard by anybody. You’re always seeking affirmation or trying to claim your status. You’re arguing. There’s “wisdom” and it’s not knowledge, because it’s just what people say, right?

Stably: Yes, bragging, always fighting. Everything’s an argument.

Jerry: There’s a lot of bragging. This all is in conflict with literacy. The point is – and what created the Axial Age, according to Mir, – that writing made you focus on one thing. When the world changed from oral to visual, rather than being immersed into this giant sphere of sensorium where everything is happening to you at once and you are immersed in everything, – you moved in being completely focused. Focusing on one thing was impossible in the oral world, because, you know, you’d be eaten by a sabertoothed tiger.

Literacy also brought linearity: one thing comes after the next and so your thinking becomes linear, rather than just analog. Mir talks about the separation of the knower from the known which is very important. It leads to abstract thinking. And it’s kind of one of the most important things. Because, before writing, there was no abstract thinking. Everything was very concrete, about concrete things. And without abstract thinking, there is no science, right?

With literacy, you get individualism, because you’re by yourself, you’re focused, you’re reading, you’re questioning what you’re reading, you’re your own person, right? And, you know, that gets you to the idea that there is a universal truth, which get you objectivity and monotheism and codified law. And so you can see how writing changes everything.

Stably: Yeah. But you don’t memorize as well.

Jerry: True. What else, Stably?

Stably: I guess – why does this all matter? Things are different in orality and literacy, and all this is interesting, but so what? You remember, when this app, Clubhouse, was a big thing, a few people talked about how this is the return of orality. I think the point was like: this is going to be different from places like Twitter and Facebook, which are just text-driven. We’re going to go back to talking. Although, if you believe in what Mir says, Twitter and Facebook are not exactly literate. They are not features of literate civilization…

Jerry: It’s what Logan called “tertiary orality”, which is seemingly text, but if you read it, it’s like: “LOL”, “ha-ha”… It’s basically speaking – it just happens to be text-based.

Stably: Yes, this is “digital orality” – this is the term Mir uses. I don’t think… I don’t know. I guess it didn’t quite work out. At least it hasn’t yet.

Jerry: No, but it’s true. If you look at the short arc of digital history, it went from static websites to blogging. Blogging was still very literate – I mean, relatively to Facebook and Twitter. And now you have Spaces and TikTok.

Stably: Yeah, I think the problem with Clubhouse was that it was too literate. It was like: you’re here to have a conversation. And nobody has patience for that. What? Am I gonna wait and listen to people for 15 minutes? Who has time? But yes, TikTok is a better example.

Jerry: Well, also Clubhouse lacked one of the advantages of digital media, which is asynchronicity, right? In Clubhouse, you had to be there – everybody at that same time. And as you said, wait 15 minutes for their turn to speak. Which is kind of a bummer, right? When you just can have TikTok.

Stably: One of the other things I remember being interesting: towards the end of the book Mir is talking about digital orality. Right before the digital sensorium kicks in… Digital speech is fragmented – it isn’t linear. There’s too much fluidity to it. You’re not really engaged in a conversation with someone, right? Because you don’t have to talk, then wait for a response, and then respond… You just type and put it out there wherever you want. And that brings me back to how horrible were the blog comment threads. If the kids remember, we’re talking about 20 years ago – maybe they can look it up on the Internet Archive… The threads in the popular blogs would eventually become insane. It would just branch out and split and split, and more and more splitting. And eventually, people were just yelling at each other and calling each other Hitler.

I think what Mir writes might be a good explanation of how the medium was the message there. You couldn’t have a conversation in these threads. It’s just not built for that. Everyone at the time thought blogs were amazing, right? They let people write things out, they were long forms, unlike Twitter now. You could write your argument out coherently and have a conversation. But it never worked in the comment threads because people just went insane immediately. I think digital orality is a good explanation of why common threads were always a shitshow. Even the best blogs had terrible comment sections.

And now, whatever Twitter is, whatever social media is, it’s just that. All the time. It’s completely impossible to have a conversation without immediately devolving into a screaming match and name-calling. A part of that is just what people think Twitter is for. But I think the point is this is what digital speech does, right? It’s just too fragmented. It literally makes people anxious and angry. I found that very interesting.

Jerry: Yes, it puts you into a mindset where the incentive is to be acknowledged and to have your status confirmed. And there’s no conversation to be had. You’re just trying to, you know, to confirm who you are and that you belong to the right tribe. And that’s it, right? There are no ideas here. There’s no content.

Stably: Yes – and even when you try… Because not everyone is out there for the clicks, although most people are…

Jerry: But if you trying to get an idea across, you probably aren’t going to be using Twitter.

Stably: Yeah, I guess. I mean, maybe that’s what people are figuring out or deciding on now. But still, at least according to Mir, it’s just the structure of it. It’s impossible, it’s just not going to happen.

Jerry: Yeah, but social media is where everybody is, right? That’s where the audience is. That is why even people who are trying to put ideas out – they find themselves having to go there. But then what is happening is that when they write something long and they put it on Twitter, the only thing that actually gets read and shared and discussed on Twitter is the headline. And the photo accompanying it maybe. And so, your long idea just becomes an instrument for whatever agonistic saga is going to happen on Twitter.

Stably: Yes, yes. Basically, the internet is making us stupid.

Jerry: There is another thing that has occurred to me reading this, but I haven’t articulated it yet. Jaspers’ point is that all of history – from prehistory, through the Axial Age, and now to world history – this ark of history is all progressive, right? He didn’t foresee this reversal. It’s all progressive, and it basically culminates in the greater unity of humankind, where eventually we all will be one. And here we get to what Mir says about, which involves the “S-word”: Singularity… Which comes a little bit out of nowhere for me. But what’s interesting, one of the axial civilizations is Buddhist. And as you know, Stably, I am a rank amateur adept.

Stably: Oh, here we go…

Jerry: Yes. But the thing about Buddhism is that it’s trying to get you to recognize your true nature. Which is basically: there’s no you, there’s no individuality…

Stably: There’s only Zuul.

Jerry: There’s only Zuul… That’s basically if you stop and really pay attention to your sensorium you will notice that it’s not linear, that basically everything is happening at once. And that there’s actually no you and me. We’re all one. I mean, I’m bastardizing it and making it fit. But it’s kind of interesting that you had this ancient kind of idea, right? What I’m trying to say is that what Jaspers has in mind, – and what I read in Mir’s book – is that, in order to get to a place where humanity can recognize that it is one and that there’s unity, it has to go through individualism first.

Here is the quote from Lenin that Mir uses:

“Lenin said on another occasion: ‘Before uniting and to unite, we must first decidedly separate from each other.’ Jaspersian humankind is not a faceless mega-tribe or a hive-like collective; it is a political, cultural, and moral unity of autonomous nations made of autonomous individuals.”

Anyhow, I think there’s something here that resonates deeply with Buddhist thought. So, I wanted to say that. You just have to recognize that we are already one, whereas Jasper seems to think that we’re going to become that. And the singularity kind of gets to it, right? So, maybe we should jump to that.

I’d love to hear what you think about this. To me, it jumps kind of out of nowhere; you tell me if you saw it coming. But Mir basically says that the Axial Age is actually a parenthesis. It’s not just continuous progression for humankind, but it ends up with our return to orality, which he calls the Axial Decade, because it happens very quickly. The Axial Age was just kind of a parenthetical thing between orality and orality. And what’s happening now is Axial as well. AI is going to basically become a new species. Maybe merged with us, maybe not – and it’s just the beginning of a history for a new species. Am I characterizing that correctly?

Stably: Yes. I mean, it’s a little confusing, right? All this talk is kind of fuzzy and strange if you asked me, but yeah, I think that’s what he’s positing. I’m not sure what to think of it. I think you’re right: it does kind of come out of nowhere.

Jerry: Right, at least it wasn’t given as much treatment as the other nine-tenths of the book.

Stably: Yes. I don’t know what to think of that stuff. This is his futurism. He’s put on his futurism hat. I guess we’ll know sooner rather than later if he’s right. He’s saying it’s going to happen soon. He doesn’t know how, he doesn’t know where, and he doesn’t know by whom, but it’s going to happen – it’s kind of inevitable. Because, you know, he’s a media ecologist, right? This is kind of not deterministic per se, but this is where it’s all leading. I don’t know… I mean, there’s no way of knowing how would people communicate, when you’re just your thoughts. I guess you’d have to read a bunch of cyberpunk novels or something to figure out how would this actually work. Because if you’re all plugged in, it’s like you’re in the matrix or whatever… How would people communicate?

Jerry: Yes, I don’t know. The neurons in the brain – how do they communicate?

Stably: With electricity? But we don’t even know how that works.

Jerry: Yeah, but my point is that we are already neurons, right? We’re already part of a greater whole. You may not recognize it as communication, but if you take a step back, you will see something that you can identify as an organism. The neurons don’t know that they’re part of a brain.

Stably: Sure. I mean, it’s fun to talk. I guess we just wait and find out. Anyway, there is not so much that you can’t do about it as an individual.

Jerry: True. One another thing, if I had to be a little critical… Mir makes a lot of assertions. And what he’s saying makes intuitive sense. But I have no idea – is this science? Is this based on archaeology and anthropology? I wish I had some examples of this. He would just say, you know: when you start reading, you’re more visual. And if you’re more visual, you’re more linear. Okay, that totally follows. But, like: is that true? I don’t know. It’s like evolutionary biology. It does have incredible explanatory power, but is it true? It is impossible to do the experiments, right?

Stably: Yeah. Most of the people he cites are media theorists or media ecologists – people like McLuhan and Logan. I mean, we tried to read, but we haven’t read a lot of their works. So are they citing science?

Jerry: …We’ve read Postman.

Stably: Sure, that’s true. But, you know, that was a polemic, right? But are they citing “hashtag THE science”? Or is it just the kind of things that is fun to say? Which is always my fear, or concern, about stuff like this. You can spin out a theory that sounds right – but a lot of things sound right and they’re not true. That’s always in the back of my mind. I think that is people’s concern with Jaspers. That sounds right, sounds plausible – but is that actually true?

Jerry: Yeah, it’s very intuitive. Which is fine…

Stably: Right. He is citing real people. They’re not scientists, but they’re humanists. They do not make things up, but…

Jerry: He also refers to real history. He talks about the pirates in the Mediterranean and the horses domesticated by the people of the Steppe. This is history and archaeology and all that, but then there go conclusions that these people had different affordances and experienced different media effects that led to more opportunistic behaviour… And you like: okay, that’s probably true, I guess… Anyway, it’s media ecology. I’m not saying he is wrong. I think that’s true, especially about some of the specific claims that “that caused that” or “this probably caused this”. When it comes to practical application, it makes perfect sense to me because it has predictive power for what’s happening right now. I can see it. And, you know, I can see what’s happening in the world, Mir explains it, and it even helps you predict. However he got to that – that’s very useful.

Stably: Yeah, maybe there are people like this. Like we are a real communication department, we do this research, and it’s not just a joke but we are real scholars. We can do some sort of well-crafted study that tries to get a little bit closer to the truth. So I don’t want to poopoo the whole thing… When he starts talking about the current media ecology, digital speech, its effect on people… I can see that in myself. I can see that in other people, and how you interact with them using those tools. That seems to make sense. You can get easily frustrated or you get a lot of bragging…

Jerry: …Donald Trump is the avatar of our age.

Stably: Oh, god… Yeah. I guess we’re doomed. It’s a race between this “digital sensorium” and just the nuclear launch.

Jerry: Yes. Alright, well, it sounds like we both enjoyed it very much. Recommend it?

Stably: Yes, definitely recommend it. There’s a lot to think about, there’s a lot you can argue with people about if that’s what you’re into. And the author – our friend, Andrey – he’s very enthusiastic about this stuff. And it comes through. It doesn’t look like he’s doing this to just make a book or fill on the YouTube lecture circuit. I think that all comes through. Maybe it sometimes helps to not have an editor.

Jerry: Yes, I think this is totally a passion project, for sure.

So maybe we can end with one of his observations that has just really stuck with me. I see it everywhere. Mir says:

“Interestingly, digital media retrieve, or rather reinforce, the inclination of humans towards loud self-exposition, innate in orality and antonymous to the inward turn. For example, as has already been mentioned, talking on a cell phone with speakerphone on transforms phone conversation into speech-behaviour typical for orality. A phone conversation with the responder’s voice being broadcast into the surroundings despite no practical need for it is a feature of oral outwardness with its absence of private spaces.”

And so – you’ve seen this, right? This is on the rise. You’ve seen people walking around, especially in a supermarket, with the conversation on speakerphone. Or oftentimes it is a FaceTime call, with video, but they’re not looking at it. They’re just holding it up with the speaker towards their mouth. So, they’re pointing up to the ceiling. And when I look at the phone, the video coming through on the screen that the other person is sending is also have like a closet door and not a face. And they’re just talking.

Stably: And you think this is happening everywhere… So, what is his explanation?

Jerry: I don’t know what it is.

Stably: I guess maybe people like it? Because it lets you just blabber on?

Jerry: It lets you blabber on. It lets you broadcast to the world that you’re important because you have somebody to talk to you. Whatever you’re talking about is probably going to include a lot of bragging so that people can hear, etc.

Stably: Yeah. My special lady-friend watches a lot of Bravo programming – a lot of “Housewives”. And the housewives all communicate like this.

Jerry: Well, but I imagine it is because TV requires the other end to be heard, right? Maybe that’s where it starts?

Stably: But it’s on FaceTime. It’s never just a speakerphone, it’s always FaceTime. Obviously, you have to have the conversation out loud for TV. But it’s funny that it’s not just speakerphone. It has to be with this other guy’s face staring at you, but you’re holding the phone, like you said, at an angle and talking into. So, you’re not even using it as a phone. I’ve always wondered why they do that…

Jerry: All right. Well, Stably, we enjoyed the book. We recommend it to people…

Worker and Parasite Podcast, January 30, 2024.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

- Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

- Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020)

- Human as media. The emancipation of authorship (2014)

Categories: Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror, Digital orality, Emancipation of Authorship, Future and Futurology, Media ecology, Media literacy, Postjournalism and the death of newspapers, Singularity and Transhumanism

Leave a comment