Piracy prepared the Greek minds for the effects of the alphabet. This might explain why the alphabet effect in Greece was so instant and so transformative. A chapter from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

This is the first section of the chapter: Pirates and the opportunistic mentality.

Pirates and the opportunistic mentality

In 20 years of the Trojan War and a drawn-out return home, Odysseus encountered more events and endured more suffering than agrarian men would have experienced in 20 generations. While Odysseus’ journey back home was indeed particularly outstanding, as he found himself between a rock and a hard place of gods’ favour and wrath, a high frequency and intensity of events in the life of a seafarer was not unusual. The lives of Odysseus, Sinbad the Sailor, and Robinson Crusoe were full of remarkable adventures. Odysseus was a king, Sinbad was a merchant, and Robinson was a commoner, but seafaring dragged them into ventures involving looting, the slave trade, and banditry – in one word: piracy.

For a pirate, a change of scene was an essential prerequisite of the trade. However, it wasn’t just a change of scenery; it was also a change of prospects. The gains in the business could be plentiful, but the losses could also be ultimate, leading to captivity, slavery, or death. Such a variability of outcomes made the seafarer a venture capitalist investing in a risky business, where his main assets consisted of his luck and inventiveness and his stakes were his own fate and life.

Soviet philosopher Mikhail Petrov (1923–1987) advanced a theory about the role of piracy in the “Greek Miracle.” In his 1966 essay Pirates of the Aegean and Individuality, Petrov suggested that the ancient pirates introduced a new type of mentality principally contrarian to the mentality of cultures based on irrigation.

According to Petrov, the first agrarian civilizations, including those of Ancient Egypt, Babylonia, China, and Minoan Crete, were the “Olympian civilizations,” as he called them. Unlike the previous clan systems, in which tribe members received their names as professional and social instructions, the more developed agrarian societies dissociated the names-instructions from individuals, granting people a bit more freedom. Instead, the names-instructions were assigned to gods, who became responsible for various trades. The variety of gods, with their divine attributes, covered the entire spectrum of natural occurrences and human relationships.

Olympus, the mountain where the Greek gods dwelled, represented the division of labour and also the division of knowledge. As a pantheon, Olympus was, according to Petrov, “a mnemonic device that helps society orient its members in the world-cosmos and raise new generations in accordance with the legacy of the past.”[1]

In other words, Olympus (or any developed pantheon of gods-specialists) served as a device of memorization, instruction, and indoctrination and was clearly another “tribal encyclopedia,” as Eric Havelock called the Homeric poems just three years before Petrov wrote his essay (with Petrov, a Soviet WWII veteran and philosopher-dissident, having not a single chance to know about Havelock’s existence).

Havelock, by the way, also noticed that natural and human relationships were “recorded” in the relationships of gods. He writes:

So the gods do indeed become a kind of apparatus organised in families on the analogy of men, and they have personal attributes that remain fairly constant. For a given phenomenon, a given god becomes appropriate (though Homer shows some flexibility in his choices) and these divinities in order to be remembered with constancy themselves become incorporated in their own saga, so to speak. They love and quarrel, rule and obey, in situations and stories which imitate the human political drama. Their stories thus in turn become paradigms of the operation of the public and private law which it is the business of the saga to preserve. They constitute a second society superimposed upon the society of the heroes.[2]

Looking for an explanation for the “Greek Miracle” – the Greek Enlightenment of the 5th–3rd century BCE – Petrov tried to detect in Greece something that wouldn’t conform to the rigid patterns of Olympian divine instructions. Petrov writes:

Examining the skills of a Greek in the Homeric period, we need to exclude most of them as inherently ritualistic due to their cyclic and repetitive nature, fixed in the patterns of experience, and therefore oriented towards the past. The only exceptions are seafaring and piracy. Here, repetition, rigid patterns, and a lack of originality and initiative in handling situations would be a straight way to die. In essence, each raid becomes an act of creativity, where traditional and novel approaches are combined in new ways, each time derived from the circumstances.[3]

Seafaring and piracy, therefore, were exceptions from the otherwise ritualistic division of labour in ancient societies.

Despite all irrigation civilizations belonging to the same Olympian type, Petrov contrasted the Minoan civilization of Crete with China. The distinction was “geo-political.” The inland isolation of China decreased the risks of invasion; also, the centralized administration learned to deal with invasions when they occurred, as evidenced by the construction of the Great Wall some time later. Seashores, on the contrary, were open to pirates who appeared and vanished momentarily. Piracy did not require organizing large armies. A ship with 50–60 oarsmen, who were also well-trained and well-armed bandits, could easily rob a village and escape before the arrival of the regular forces.

Therefore, as Petrov writes, the Chinese statehood was “hydrotechnical”: it focused on harnessing seasonal and river cycles for agriculture. Minoan statehood focused on the protection of agricultural products from looters coming by the sea. This is why the Minoan leader was a warrior, while the leading figure in Ancient China, as well as in Egypt and Babylonia, was the “minister of solar eclipses,” as Petrov calls it – a high priest responsible for the due cyclicity of natural processes.

Additionally, river behaviour, the main concern of the inland civilizations, was a highly regular phenomenon. The knowledge of the past and the successful past patterns of behaviour determined success in the future. This necessarily past-based regularity was at the core of agrarian ritualism.

On the other hand, the main concern of the coastal civilization was sea behaviour. While the sea itself could be predictable to a certain extent, piracy was a highly irregular factor. Nobody could know when and where the pirates would strike again. This environmental specificity disfavored any ritualistic cyclicity and rituals in general. Piracy, according to Petrov, was the only trade that could not be ritualized. The irregularity of piracy affected the mentality of both coastal dwellers and the pirates themselves. Moreover, they were often the same people: the defender of a seashore village against pirates could easily go on a pirate raid the next month.

Minos, the semi-legendary ruler of Crete, was reportedly the first historical figure to build a navy; he was also known for suppressing piracy. However, some accounts suggest that these so-called efforts to suppress piracy were rather attempts to simply regulate it. Sea nations would make treaties not to raid the shores and ships of each other. Otherwise, occasional or professional piracy was a usual occupation of seafarers. The kings in the Homeric poems habitually bragged about past raids and rich booty.

The innovative state of mind was the distinctive feature of people living at sea and by the sea. Petrov notices that inventive Odysseus could plot, with equal facility, the capture of Troy with the use of a giant wooden horse, the escape from the Cyclops by tying himself and his men under the bellies of the Cyclops’ rams, and the killing of Penelopa’s suitors after a contest manifesting his true king’s right. Along the way, Odysseus would not forget to steal some rams and goats from the Cyclops.

The common epithet for Odysseus was “cunning”; his cleverness was often highlighted. In Greek, however, the main quality of Odysseus was referred to as polytropos, which meant not so much “smart” or “clever” but “of many turns.” The intellectual qualities the Greeks valued in Odysseus were his outstanding inventiveness and versatility, his ability to elaborate a winning strategy for an unprecedent task.

Thus, the repetitive nature of inland life and the adventurous character of life at sea contributed to the formation of ritualistic or opportunistic mindsets, respectively. The virtue of the agrarian mind was following tradition, while the virtue of the seafaring mind was versatility and opportunism.

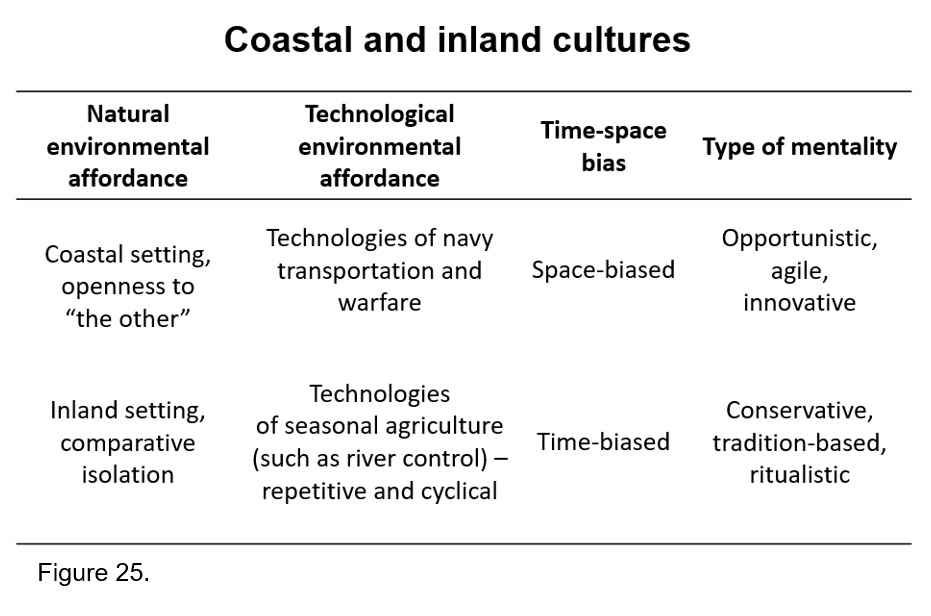

This wasn’t solely a matter of choice or cultural legacy; such were the environmental affordances of life inland or on shore. The environmental affordances of coastal and inland living were both natural and technological. The natural affordances were formed either by inland isolation or by seashore openness. The technological affordances were formed either by season-based agrarian technologies or by the technologies of sea travel.

In Innis’ terms, irrigation civilizations were time-biased, as they sought to preserve successful patterns of the past over time, while sea civilizations were space-biased, as it was “afforded” for them to explore new opportunities overseas, and the temporal parameter of cyclicity did not play a significant role.

The division between continental and coastal mentalities can fuel large geopolitical theories, such as a conspiracy theory about the perpetual conflict between “Atlanticism” and “Eurasianism,” popular among Russian conspiracists ranging from the émigré Nikolai Trubetzkoy in the 1920s to Alexandr Dugin, an alleged ideologist within Putin’s regime. Some Western geopolitical theorists, like Zbigniew Brzezinski with his “geostrategies”[4], also expressed compatible ideas. According to this theory, for example, the astute Atlanticists deliberately pitted two major inland powers, Germany and Russia, against each other in both World Wars. The Cold War can also be seen as a continuation of the conflict between Atlanticism (the coastal mentality) and Eurasianism (the inland mentality).

Signs of the opposition between continental-ritualistic and coastal-opportunistic mentalities can be traced even in American elections: the inland so-called “square states” lean more towards traditions and conservatism, while the “coastal states” tend to be more progressive.

The ancient Greeks belonged to coastal cultures and leaned towards the opportunistic mentality developed by seafarers and pirates.

Next:

A chapter from Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect.

See also books by Andrey Mir:

- Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror: Jaspers’ Axial Age and Logan’s Alphabet Effect (2024)

- Postjournalism and the death of newspapers. The media after Trump: manufacturing anger and polarization (2020)

- Human as media. The emancipation of authorship (2014)

[1] Petrov, Mikhail. (1995 [1966]). Pirates of the Aegean and Individuality, Ch. 2.

[2] Havelock, Eric. (1963). Preface to Plato, p. 170-171.

[3] Petrov, Mikhail. (1995 [1966]). Pirates of the Aegean and Individuality, Ch. 6.

[4] See, for example: Brzezinski, Zbigniew. (1997). The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives.

Categories: Digital Future in the Rearview Mirror, Media ecology

Leave a comment